software as a craft

9/28/2024I am far from being the de facto authority on programming - if anything, I’d describe myself as an eternal beginner. Building software is a skill that is infinitely broad and difficult; I start over as a novice almost every day. This field is vast, there is a never-ending deluge of new technologies, topics, and paradigms to master.

Yet still, people often ask me “What should I do to get good at programming?” This essay is my attempt to answer that question. My belief is simple: By keeping certain principles as your north star, eventually, you will reach the destination you desire.

carpentry and code

I believe that software is a craft.

An activity or undertaking of a skilled nature; a pursuit requiring the acquisition and application of specialist knowledge.

– Oxford English Dictionary

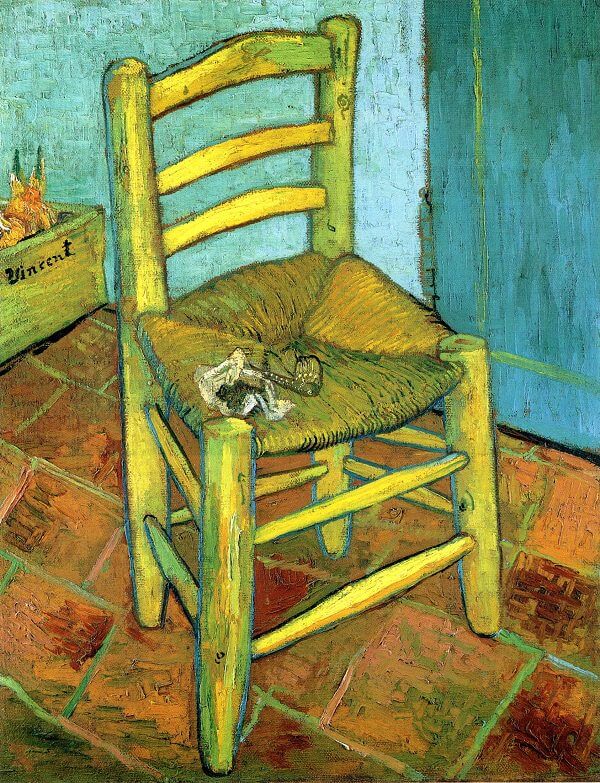

What do I mean by the statement software is a craft? Let’s compare it to a traditional craft like carpentry. While building a program isn’t a physical craft like carpentry, it is easy to draw parallels between them.

In carpentry, there are many steps. Greatly simplified, when a carpenter is making something it will include the following steps: planning, designing, selecting materials, preparing, shaping, assembling, and finishing.

For anyone familiar with building software, these steps sound familiar. Although you are molding zeros and ones instead of wood and writing lines of code instead of cutting up chunks of wood; both carpentry and software engineering start from scratch and end with a product with a purpose.

Carpenters make chairs; software engineers build programs.

venn diagram

It is important to note that software is a craft and not an art. A craft implies the result is made with a purpose; an art’s purpose is to express something from the maker to the receiver.

As you might’ve noticed, under this definition, arts are a subset of crafts. some crafts are art, but crafts are not exclusively art.

A carpenter can make both arts and crafts; both intricate wood carvings and support beams for a home. Programmers can create anything from virtual donuts to government infrastructure.

This distinction is important, it’s something that guides your approach to your work. While an artist focuses on how to conjure a feeling most accurately, a craftsman will often need to be more pragmatic in their considerations.

time in, skill out

“If people knew how hard I worked to get my mastery, it wouldn’t seem so wonderful at all.”

– Michelangelo

Just like any other craft, mastering programming requires time, practice, and dedication. When you watch someone deeply proficient at a skill it will seem trivial, but what you don’t see are the countless hours spent honing that skill.

It sounds obvious, but becoming great at something takes an enormous amount of time. Such a long time that it is difficult to fathom. However, the inverse is also true. All skills can be bought, the currency is just time, not money. Programming is no different.

While I can’t promise you will be great within a year, two, or even five; I am certain that if you dedicated your life to any skill for ten years, you will be at the 99th percentile by the end. It is only human to overestimate how much you can improve in one year, but severely underestimate how much you can improve in ten.

Internalize this and make small strides every day.

joy in the process

Although you should put time in, it doesn’t mean torturing yourself. If each and every line of code feels like stepping on a nail; forget about improving, you won’t ever even sit down in front of a keyboard.

Humans are simple creatures, we are easily influenced. Just as placing fruit within easy reach encourages healthier eating habits, finding little bits and pieces of programming you love will make you spend more time programming. As we’ve established, time = skill, so anything you can do to make you spend more time programming will inevitably make you better.

There are a multitude of ways you could go about this, and everyone has their own little things about it they love.

The parts I love about programming are plentiful: trying out all the newest tools and editors (currently using Codeium + Neovim!), building out fun things I had imagined, figuring out a funky way to do something through trial and error, and carefully perfecting a feature.

But don’t just take it from me, take it from them.

DHH, most well-known for making Ruby on Rails, is someone I disagree with about many things; but it is difficult to deny he is great at programming. The parts he loves about programming are all the magical little moments, he puts the tools that make him feel that way at his fingertips. He describes using vi as inputting Hadoukens and Ruby as something that turbocharged his productivity.

When we were out for lunch, I asked Giles, my team lead, about what kept him as a hands-on keyboard developer for 20+ years who still deeply loved programming, he answered:

There are a lot of things I love about programming… the learning and problem solving aspect, but I think that a big reason I’ve kept programming for all these years is that feeling of flow I get when I’m coding. The only thing comparable I’ve experienced is playing an instrument.

I could bore you with more testimonials, but instead I’ll leave you with this. Improvement is impossible if you hate every step, but if you find joy in the process it will be as inevitable as a ball rolling to the bottom of a hill.

build with a purpose

In reality, the hill is more bumpy than smooth, and you won’t be instilled with a sense of awe for every line of code you write. While you should make the process as enjoyable as you can, there will be a significant portion of the process that is more mundane. Writing tests, reviewing code, and fixing a cryptic bug are not activities I’d describe as glamorous or fun.

In times like these, it’s important to keep the bigger picture in mind. Be a pragmatist, and fulfill your responsibility to the user. Take pride in your work and ensure each and every aspect of the software is as it should be.

It’s often the most painful and unwanted tasks that make good software great, but it’s equally apparent when corners are cut and you are left with the equivalent of digital garbage. This unglamorous work is just as much a part of the craft as the enjoyable parts.

While an art piece may be ruined by a single stroke drawn without passion, a precisely hammered nail, even by a bored carpenter, has never caught criticism. At the end of the day, when you see what you built not as its individual pieces but as the sum of its parts, you can reap the rewards of your grueling efforts.

closing

My short answer is “code more and you’ll get better” but I believe that my long answer as written here is far more insightful. It’s easy to tell beginners to “do and improve” but the reason for that is often not so clear. Learning something new is very daunting and difficult, and it’s hard to know where you should even be going. In times like those, I hope that readers of this post (and myself!) can keep these principles in mind when striving to improve.

Writer’s Note: I’d like to thank and credit Giles as much of the inspiration behind this post. Much of this post is inspired by his comparison between good software and “making the right cut on a block of wood.” The idea has been stuck in my head bouncing around ever since.

I hope that my writing is half as insightful and interesting as the advice he gave me.